Welcome back to the A Little Wiser newsletter! Thank you to everyone who continues to support us. To show our appreciation, we’re officially launching a referral system featuring exclusive ALW gifts! You’ll soon get your own personal link and a rewards tracker to see exactly how many people you've brought into the fold. Today’s wisdom explores:

How Self-Driving Cars Work

The Japanese Salaryman

How Nuclear Waste Is Stored

Grab your coffee and let’s dive in.

TECHNOLOGY

🚗 How Self-Driving Cars Work

At their core, autonomous vehicles are rolling data centers. A modern self-driving car relies on a layered perception stack: cameras to read traffic lights and signs; radar to judge distance and speed in rain or fog; and lidar, which fires millions of laser pulses per second to build a live 3D map of the environment. All of this sensory input feeds neural networks trained on billions of miles of driving data. One autonomous car can generate up to four terabytes of data per day, roughly the same as several thousand people using the internet at once. Driving, it turns out, is not a single skill but three: perception (what’s around me), prediction (what will it do next), and planning (what should I do now).

This is where different philosophies diverge. Companies like Waymo use all three major sensors (cameras, radar, and lidar) betting that redundancy equals safety. Tesla, by contrast, has chosen a camera-only approach, arguing that humans drive using vision alone and machines should learn to do the same. Critics argue this removes a crucial safety layer, especially in low-visibility conditions. In controlled urban environments, autonomous vehicles already show accident rates significantly lower than human drivers and researchers estimate full autonomy could eventually save over a million lives a year. But getting from impressive demos to universal trust is the hard part; a study by the Harvard Kennedy School found that nearly 7 in 10 Americans admit they would feel less safe sharing the road with an AI-driven truck. Companies are working to fight this sentiment as autonomous systems log thousands of hours of simulation, replaying the same dangerous intersections until the safest response becomes statistically dominant.

Analysts estimate the autonomous vehicle market could exceed $1 trillion annually if deployment spreads across ride-hailing, freight, and logistics. But economists also warn of disruption on a historic scale. Millions of taxi drivers, delivery workers, and truckers sit directly in the path of automation. Regulatory caution, rare but high-profile accidents, and the sheer complexity of urban environments mean autonomy will spread city by city, not all at once. The destination is clear, but the journey, fittingly, remains carefully navigated.

The tech inside a self-driving car

CULTURE

🏢 The Japanese Salaryman

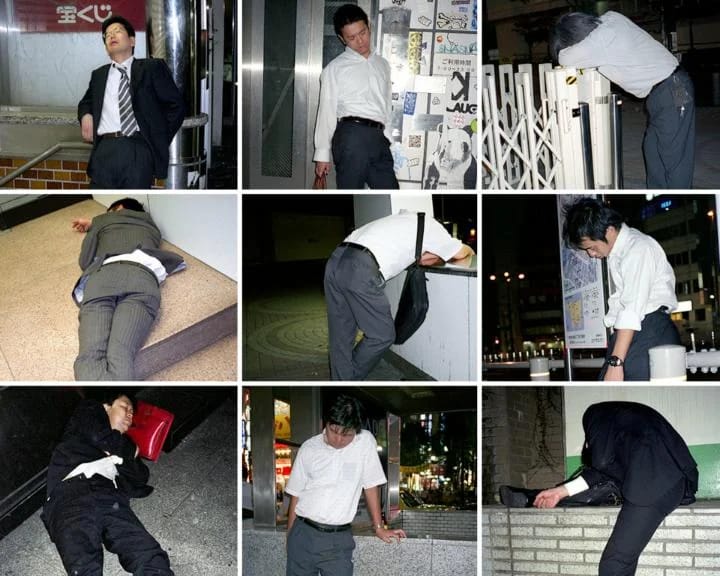

For decades, the Japanese salaryman was the human engine of one of the world’s largest economies. Dressed in identical dark suits, commuting in silence, he embodied a postwar social contract: absolute loyalty to the company in exchange for lifetime employment. Hours were long, evenings often dissolved into mandatory drinking with colleagues known as ‘nomikai’, and the last train home at midnight became a daily deadline rather than an exception. Falling asleep at your desk, inemuri, was not shameful but symbolic. It meant you had given everything. Japan rebuilt itself on this ethic, and for a generation, it worked. Productivity soared, exports dominated, and corporate stability became a national virtue.

But the system extracted a cost that statistics now struggle to hide. A recent McKinsey Health Institute study found only 25% of Japanese employees report good overall well-being, the lowest score of any country surveyed. In 2025, nearly 45% of full-time workers identified as “quiet quitters,” doing exactly what their job requires and nothing more. A new group has emerged with a name that would once have sounded heretical: Hodo Hodo Zoku, the “So-So Tribe.” These workers deliberately refuse promotions, avoiding the punishing lifestyle of the middle manager crushed between senior expectations and junior workloads. The salaryman ideal, once aspirational, has become a warning label.

The economy around overwork still hums quietly at night. Miss the last train and you don’t go home but disappear to sleep in Tokyo’s shadow infrastructure: capsule hotels and 24-hour manga cafés. Yet cracks are spreading. Microsoft Japan famously trialed a four-day workweek and saw productivity rise by 40%. In 2025, Tokyo’s metropolitan government rolled out a four-day option for civil servants, aiming to keep women in the workforce and slow demographic decline. Japan’s salaryman is not vanishing, but he is evolving. In offices across Tokyo, a generation is finally asking the most disruptive question in Japanese corporate history: what is all this work actually for?

Polish photographer Paweł Jaszczuk became world-famous for his book High Fashion, which features photos of salarymen passed out in bizarre, contorted poses on the streets of Tokyo

SCIENCE

☢️ How Nuclear Waste Is Stored

Nuclear power is often sold as clean and compact: a small amount of fuel producing enormous energy with almost no carbon emissions. What is less often said is that the waste it leaves behind refuses to fade on any human timescale. High-level nuclear waste remains hazardous for tens of thousands of years which is longer than any empire, religion, or written language has reliably endured. This turns storage into a problem not just of engineering, but of civilisation. We are, quite literally, trying to design systems that must remain safe for longer than history itself.

In the near term, the solution is surprisingly mundane. Freshly used fuel rods are so hot and radioactive that they spend their first 3 to 5 years submerged in deep pools of water at nuclear plants. The water cools the fuel and blocks radiation. Once the heat subsides, the waste is transferred into dry cask storage: enormous steel-and-concrete cylinders weighing over 100 tonnes, built to survive earthquakes, floods, fires, and direct impact. These casks have an excellent safety record and can sit quietly for decades. But they are not the endgame as the long-term plan for most nuclear nations is deep geological storage: sealing waste hundreds of metres underground in rock formations that have remained stable for hundreds of millions of years.

Finland is furthest along this path. Its Onkalo repository is carved into two-billion-year-old granite and is designed to remain sealed for at least 100,000 years. Inside, spent fuel will be locked into copper canisters because in oxygen-free underground conditions, copper corrodes so slowly it may last over a million years. Those canisters are then wrapped in bentonite clay, which swells when exposed to water, sealing cracks and forming a self-healing barrier. Perhaps the most haunting aspect of this project is the field of nuclear semiotics ‘the art of warning the future’. Scientists are debating how to signal danger to a humanity that may have forgotten our alphabet or even the symbol for radiation. There have been proposals like the "Landscape of Thorns," consisting of jagged concrete pillars designed to evoke an instinctive sense of unease. Another is the surreal "Ray Cat" theory, which suggests genetically engineering cats to change color near radiation and weaving their legend into global folklore. As we seal these vaults, we are writing a message to the future in a language we have yet to invent, hoping that "out of sight" truly remains "out of mind" for the next thousand generations.

We hope you enjoyed today’s edition. Thank you to everyone reading, sharing, and helping A Little Wiser reach new people every week.

Until next time…. - A Little Wiser Team

🕮 Three lessons. Three times a week. Three minutes at a time.

💌 Enjoyed this edition? Share it with someone curious.