Welcome back to A Little Wiser! Our referral program is officially live. At the bottom of this email, you’ll find your personalized link to unlock our new reward tiers, ranging from exclusive ALW merch to the chance to request a specific lesson for a future issue. Every time a friend signs up through your link, you move one step closer to the next reward.

Petra: The Rose-Red City Carved in Stone

What Happened to Blimps

The Rise of Starbucks

Grab your coffee and let’s dive in.

HISTORY

🏛️ Petra: The Rose-Red City Carved in Stone

Deep within the jagged, wind-scoured canyons of southern Jordan lies one of the seven wonders of the world. Petra was the capital of the Nabataeans, a shadowy tribe of nomads who swapped their tents for stone palaces and became the ultimate middlemen of antiquity. Positioned at the crossroads of the Silk Road and the incense routes of Arabia, they controlled the single most valuable commodity of the ancient world: frankincense, worth more per ounce than gold and burned in every temple from Rome to Jerusalem. For nearly six centuries, the city remained hidden from the Western world, guarded fiercely by local Bedouin tribes. It wasn't until 1812 that Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, disguised in robes and speaking fluent Arabic, tricked his way past his guide to reveal the rose-red city to Europe.

How do you build a thriving metropolis in a place that receives less than six inches of rain per year? The Nabataeans solved this with hydraulic engineering centuries ahead of its time. They carved miles of terracotta pipes into canyon walls at a precise 4-degree gradient to prevent sediment buildup while maintaining steady flow. They understood the Bernoulli Principle, the physics of fluid pressure, before it was formally named in a European laboratory. By capturing seasonal flash floods in hidden reservoirs and distributing water through a pressurized grid, they maintained lush gardens and public fountains that shouldn't have existed. Water became their strategic asset, forcing every passing traveller and merchant to pay exorbitant fees for the privilege of a drink and safe passage.

Petra's decline came as a slow-motion casualty of shifting geography and catastrophic geology. When Rome expanded maritime routes through the Red Sea, travellers bypassed the arduous desert trek entirely, severing the economic lifeline of this tax-collector state. Then a series of massive earthquakes in the 4th century shattered the delicate pipe systems and toppled columns across the city. Without its engineered water supply, Petra became uninhabitable. What saved the monuments from vandalism was their uselessness: you cannot melt sandstone for weapons or repurpose a cliff face for new construction. Today, archaeologists estimate that 85% of Petra remains unexcavated, buried under centuries of sand and rockfall. Ground-penetrating radar reveals entire districts hidden beneath the surface. What draws a million tourists each year represents merely the entrance to a city we have barely begun to understand.

The iconic Al-Khazneh (The Treasury)

TECHNOLOGY

🎈 What Happened to Blimps

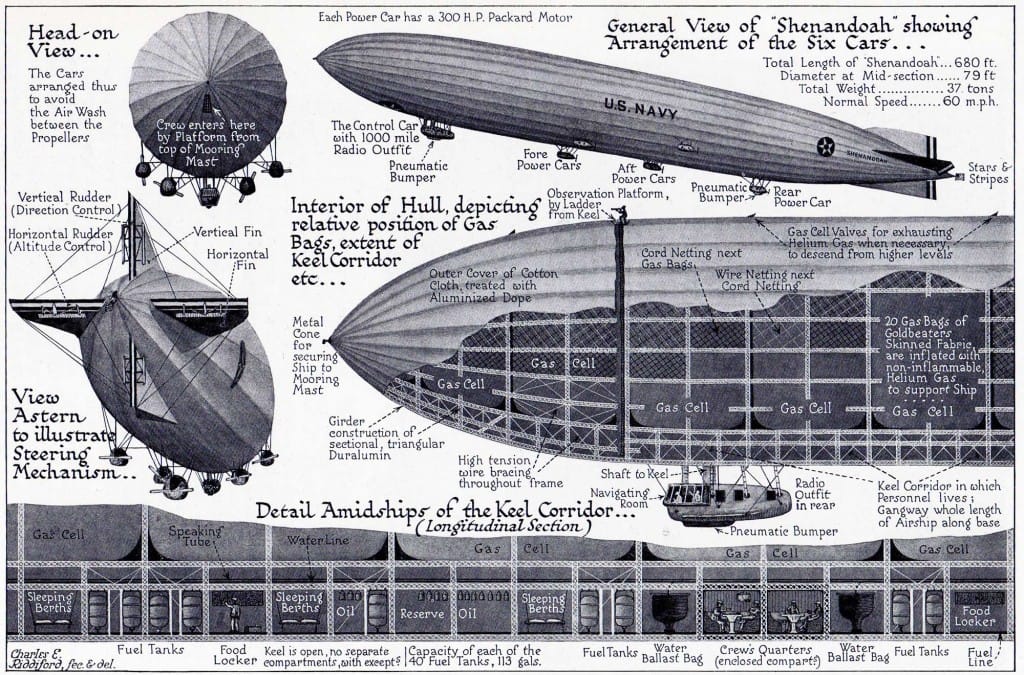

On May 6, 1937, the Hindenburg burst into flames while attempting to dock in New Jersey, killing 36 people in less than a minute. The disaster was captured on film and broadcast worldwide, within hours, the golden age of airship travel died. But this tragic event had almost nothing to do with why blimps disappeared, the real killer was economics. Airships were already losing to airplanes before the fire ever started. The Boeing 247 and Douglas DC-3 could fly faster, land anywhere with a runway, and carry passengers without requiring a ground crew of 200 men to wrestle a floating building out of the sky. The Hindenburg merely provided a spectacular funeral for a mode of transport that was already obsolete.

The physics of lighter-than-air flight explains why blimps never recovered. To lift one ton of cargo, you need roughly 1,000 cubic meters of helium, a gas so rare that the United States controls 75% of the world's supply. The Hindenburg used hydrogen because helium was expensive and restricted by the U.S. government, which refused to sell it to Nazi Germany. After World War II, helium became available but remained costly, and the fundamental problem persisted: airships are massive, slow, and vulnerable to weather. A modern cargo plane can carry 100 tons at 500 mph through storms that would ground an airship for days. The Graf Zeppelin flew around the world in 1929, but it took 21 days to do what a plane now does in 40 hours. Military experiments continued through the 1960s, but radar-equipped submarines and long-range aircraft made airships strategically pointless.

Yet a quiet renaissance is brewing in the cargo sector. Modern startups are revisiting the airship not for passenger luxury, but for heavy lifting in remote areas. Because they don't need runways and can carry massive loads of wind turbine blades or mining equipment to roadless wilderness, the economics finally align with the physics. LTA Research, backed by Google co-founder Sergey Brin, is building rigid airships again, this time filled with helium and steered by carbon-fiber skeletons. Lockheed Martin has proposed hybrid designs for Arctic mining operations and disaster relief. The age of the passenger Zeppelin died in New Jersey, but the physics of buoyancy remains one of our most efficient, untapped solutions for moving the heavy things of the world to places planes cannot reach.

Drawing of U.S.S. Shenandoah ( Rigid Airship) from the January 1925 issue of The National Geographic Magazine

BUSINESS

☕ The Rise of Starbucks

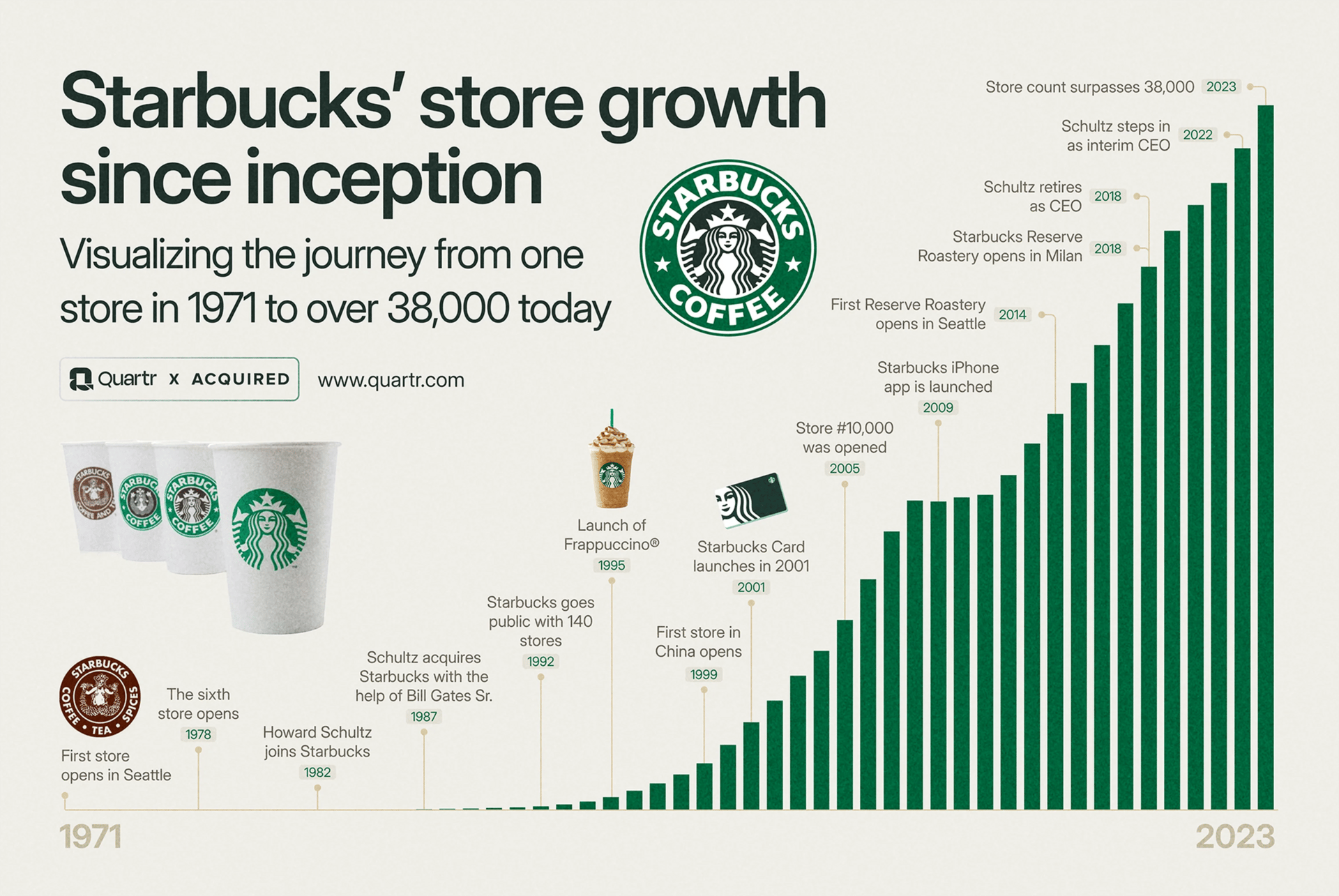

In 1983, Howard Schultz walked into an espresso bar in Milan and watched the barista pull shots with theatrical flair while customers stood at the bar, chatting with regularity that suggested ritual rather than transaction. Schultz returned to Seattle convinced he'd glimpsed the future of what Starbucks could become. But the three founders of this small chain selling coffee beans and equipment wanted nothing to do with his vision. Frustrated, Schultz quit and opened his own place called Il Giornale in 1986, serving espresso in porcelain cups while requiring baristas to wear bow ties. The concept flopped. Americans didn't want to stand at a counter drinking from tiny cups, and they certainly didn't care about the opera music he piped through the speakers. When the original Starbucks owners decided to sell in 1987, Schultz bought them out for $3.8 million in borrowed money and immediately started dismantling his own pretensions.

What Schultz built next had almost nothing to do with Italian coffee culture. He abandoned the bow ties, ditched the porcelain, and introduced paper cups sized "tall," "grande," and "venti" Italian words grafted onto an American drive-through mentality. The genius was recognizing that Americans wanted a third place between home and work where they could sit with a laptop for three hours without guilt. Starbucks stores became climate-controlled living rooms with comfortable chairs, bathrooms that didn't require purchase codes, and baristas trained to spell your name wrong on a cup, creating just enough personalization to feel special without the intimacy that might make you uncomfortable. By 1992, Starbucks had gone public.

At its peak growth in the mid-2000s, Starbucks was opening seven new stores per day globally, cannibalizing its own locations by placing them across the street from each other. The saturation strategy worked precisely because consistency mattered more than quality. A businessman in Tokyo and a student in Ohio could order the same caramel macchiato and receive identical drinks, engineered with industrial precision. By 2007, Starbucks operated over 15,000 stores worldwide and had become so ubiquitous that the company's own market research showed people were no longer impressed by the brand. Schultz, who had stepped aside as CEO, returned in 2008 during the financial crisis to find a company that had lost its way. He closed 900 locations, retrained baristas, and refocused on the theater of coffee-making, installing expensive espresso machines visible from the counter. The pivot worked, but it revealed a truth about modern retail: Starbucks succeeded not by perfecting coffee but by engineering a repeatable, exportable sense of place. The coffee was always beside the point.

We hope you enjoyed today’s edition. Thank you to everyone reading, sharing, and helping A Little Wiser reach new people every week.

Until next time…. - A Little Wiser Team