Welcome back to A Little Wiser. Thank you for everyone’s continued support, please feel free to reply with your feedback and recommend a lesson you’d like to see soon! Today’s wisdom explores:

The Science Behind Deadly Nerve Agents

The Origins of Rum

The Aeneid: Rome’s Epic Poem

Grab your coffee and let’s dive in.

SCIENCE

🧪 The Science Behind Deadly Nerve Agents

In March 2018, Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were found slumped on a park bench in Salisbury, England. Local doctors had no idea what they were dealing with as the pair were convulsing, foaming at the mouth, and their pupils had shrunk to pinpricks, classic signs of nerve agent poisoning. It took investigators days to identify the culprit: Novichok, a family of nerve agents developed in secret by the Soviet Union during the 1970s and 80s. The name translates to "newcomer" in Russian, a darkly ironic label for a weapon specifically designed to circumvent international chemical weapons treaties. Novichok agents are roughly five to eight times more lethal than VX, previously considered the deadliest nerve agent ever created, and they can be manufactured from relatively common industrial chemicals, making them terrifyingly accessible to state actors willing to break international law.

Like all nerve agents, Novichok works by blocking acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter responsible for muscle control. Without this enzyme, acetylcholine floods your nervous system unchecked, causing your muscles to contract uncontrollably. Your heart races, then stops. You suffocate while fully conscious, drowning in your own saliva as your body loses the ability to regulate even basic functions like breathing and swallowing. What makes Novichok particularly insidious is its persistence, it doesn't break down quickly in the environment. When British authorities tried to decontaminate the Skripal attack sites, they had to demolish the roof of Sergei's house, destroy his car, and dig up sections of pavement because the agent had soaked into porous materials. One woman died four months after the original attack when she sprayed what she thought was perfume from a discarded bottle, not realizing it contained enough Novichok to kill thousands.

The weapon's most high-profile victim was Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition leader who was poisoned with Novichok in August 2020 while flying from Siberia to Moscow. Navalny collapsed mid-flight, and his survival was purely accidental: the pilot made an emergency landing, and medics administered atropine, one of the few antidotes that can counteract nerve agents if given immediately. What makes Novichok so valuable to authoritarian regimes is not just its lethality but its message. Unlike a bullet or a staged accident, nerve agent poisoning is unmistakably deliberate and almost impossible to execute without state resources. It's not designed to be subtle, it's designed to send a signal. When someone is poisoned with Novichok, the world knows exactly who has the capability and the motive, even if no one can prove it in court.

HISTORY

🥃 The Origins of Rum

Sugar plantations spread across the Caribbean like wildfire after Columbus brought sugarcane cuttings to the islands in 1493. With them came an unintended byproduct: molasses, the thick, dark syrup left over after sugar crystals were extracted. For decades, plantation owners treated molasses as worthless waste, until enslaved workers on Barbadian estates in the 1650s discovered that fermenting and distilling it created a potent alcohol that could be sold for profit. They called it "rumbullion" or "kill-devil," and it tasted harsh and industrial, nothing like the refined spirit we know today. But it was cheap, strong, and didn't spoil on long sea voyages, which made it perfect for the British Royal Navy.

In 1655, the Royal Navy officially replaced the daily beer ration for sailors with half a pint of rum, a policy that remained in place for over 300 years until it was finally abolished in 1970 on what sailors still call "Black Tot Day." The logic was practical: beer went sour in the Caribbean heat, while rum stayed good indefinitely and took up far less space in the ship's hold. The daily ration, eventually mixed with water and lime juice to prevent scurvy and called "grog," became so central to naval life that withholding it was one of the harshest punishments a captain could impose. New England distilleries became the economic engine of the American colonies by turning Caribbean molasses into rum, which they then sold back to Africa to purchase more enslaved people, creating a closed loop of profit built entirely on suffering.

The cultural legacy of rum is split between romance and ruin. Pirates like Blackbeard and Calico Jack are inseparable from the image of rum-soaked Caribbean lawlessness, and the drink became synonymous with rebellion, freedom, and life on the edges of civilization. Tiki culture in the 1930s repackaged rum as escapist exoticism, while Ernest Hemingway drank daiquiris by the dozen at El Floridita in Havana, cementing rum's place in literary mythology. But behind the tropical drinks and pirate legends is a drink born from colonialism, slavery, and exploitation on an industrial scale. Modern rum production has tried to reckon with this history, with distilleries in Barbados, Jamaica, and Martinique now emphasizing heritage, craftsmanship, and the contributions of Afro-Caribbean communities who actually invented the spirit. The drink that once lubricated empires is now a symbol of the islands themselves, a reminder that even the darkest histories can be reclaimed and transformed into something the people who endured it can finally own.

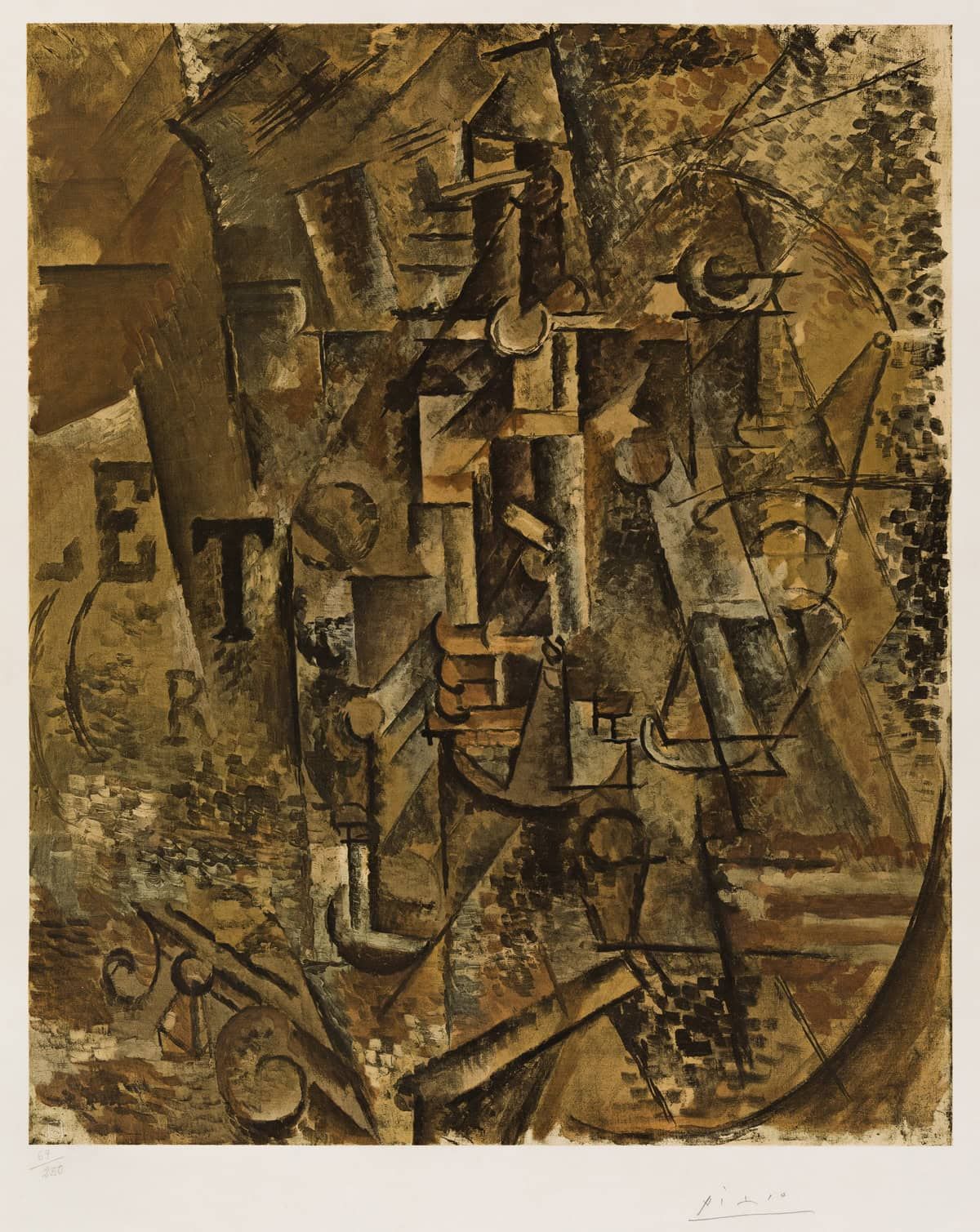

Pablo Picasso’s "Still Life with a Bottle of Rum" (1911)

LITERATURE

📜 The Aeneid: Rome’s Epic Poem

When the Roman poet Virgil lay dying in 19 BCE, he made a desperate final request to his friends: burn the manuscript of The Aeneid. He had spent eleven years writing Rome's national epic, a 9,896-line poem tracing the journey of Aeneas from the burning ruins of Troy to the founding of Rome, and he considered it unfinished and unworthy of publication. His friends ignored him, and Emperor Augustus himself intervened to ensure the poem survived. The Aeneid was pure political propaganda dressed in mythological grandeur, a story designed to legitimize Augustus's rule by linking him directly to the gods. Aeneas was supposedly the ancestor of Romulus and Remus, which made him the forefather of Rome itself, and conveniently, the Julian family (Julius Caesar and Augustus's clan) claimed descent from Aeneas's son. By turning Aeneas into the ultimate hero, destined by fate to birth an empire, Virgil was writing Augustus into divine inevitability.

What makes The Aeneid remarkable is how brazenly Virgil copied Homer's structure and then bent it to serve Rome's imperial ambitions. The poem is essentially The Odyssey and The Iliad stitched together: the first six books follow Aeneas wandering the Mediterranean like Odysseus, complete with a doomed love affair with Dido, Queen of Carthage, while the second six books are pure warfare as Aeneas battles his way into Italy like Achilles. But where Greek heroes were individualistic and often defied the gods, Aeneas is defined by "pietas," duty above all else. He abandons Dido even though he loves her because fate demands he found Rome, and she kills herself on a funeral pyre, cursing his descendants and prophesying the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage. Virgil was writing 200 years after those wars, so he embedded Rome's greatest enemy into the origin story as a tragic footnote, a woman scorned whose rage would echo through history.

The poem's influence on Western culture is nearly impossible to overstate. Dante used Virgil as his personal guide through Hell and Purgatory in The Divine Comedy, treating him as the greatest poet who ever lived. The phrase "I fear the Greeks even when they bring gifts" comes from The Aeneid's depiction of the Trojan Horse. But beneath the propaganda and the duty, Virgil embedded something more subversive. Aeneas wins, but the cost is devastating: cities burn, lovers die, and indigenous Italians are slaughtered to make room for Rome's destiny. The final scene shows Aeneas killing a begging enemy in a fit of rage, a moment of pure vengeance that undercuts the entire heroic narrative. Virgil spent his life crafting Rome's perfect origin story, and in his final lines, he quietly admitted that even divinely ordained empires are built on blood and grief.

We hope you enjoyed today’s edition! If you did, feel free to share it on social media or forward this email to friends!

Until next time... A Little Wiser Team